Seismics

Before the first bit even begins to rotate, DEA has generated a model of the subsurface to determine the best site for the borehole. The more accurate our understanding of the structure of the Earth's strata is, the higher the probability we will hit the bull's-eye.

Seismic waves pass through the geological stratum

All over the word, seismics has established itself as the most important of these methods. This technology is based on seismic waves and works rather like an ultrasound scan at a doctor's or an echo sounder used by ships. Take the example of the waves you make if you throw a stone into a lake. They also spread out in a circular direction and are repulsed if they bump into some obstacle, for example a rock. Reflection seismics work in similar fashion: the seismic waves generated through artificially induced vibrations on or near the surface move downwards through the layers of rock at speeds that vary according to the type of rock. Deep underground, the waves are reflected by the boundaries between different rock layers. By measuring the differences between the transit times of the sound waves, we discover more about the structure of the subsurface – at depths of up to several kilometres.

From a sound wave to an electrical impulse

Depending on the terrain in question, the seismic waves are generated either by specially designed vibrotrucks or by safely detonating small explosive charges in boreholes up to 25 metres deep. The waves reflected back to the surface are registered by highly sensitive sensors known as geophones, transformed into electrical impulses and transmitted to a measuring vehicle where they are recorded for subsequent evaluation.

Special ships for seismics in water

Offshore seismic surveys are carried out by marine seismic vessels. Compressed air guns suspended directly behind the vessel generate the necessary sound waves, which then travel through the water, penetrate the rock layers below the seabed and are reflected back by the boundaries between the different layers. The reflections are captured by hydrophones mounted in towed streamers of up to 12 km in length.

Know-how for shallow water regions

DEA is particularly good at carrying out technically demanding seismic surveys in transition zones where the water is too shallow for marine seismic data acquisition. Ecologically speaking, such shallows are usually ultra-sensitive areas, e.g. the mud flats of the North German Wadden Sea, the Nile Delta on Egypt's Mediterranean coast or the coasts of Turkmenistan. We have successfully carried out seismic surveys in these environmental or archaeological protection zones. If nothing else, they were a huge logistical challenge. The various seismic teams have to work simultaneously with geophones and hydrophones, generate vibrations and compressed air, and lay many kilometres of underwater cables. Data processing is just as complicated a business since the offshore and onshore signals have to be processed in a single data set.

Nature always takes priority

Onshore, in shallow water or offshore: whatever seismic survey we carry out, we always take nature conservation and environmental protection concerns into account in our close collaboration with the respective authorities, e.g. in planning the timing and course of a seismic campaign. That is why we would never do a seismic survey in the waters off Trinidad and Tobago between January and June, for example, because this is the mating period for turtles. To limit any adverse effects on humans, animals or the environment, we prepare our seismic work extremely carefully and take the nature of the local terrain into account in choosing our sound sources. We equip the vessels we use so as to minimise any damage to crops, roads and paths. Seismic surveys do not result in any changes to the environment in question since we take all equipment and cables with us once the job is over.

2-D seismics provides a cross-section of the rock strata

If we use conventional 2-D seismics, all the seismic signal sources, geophones and hydrophones are positioned in a single line. Once evaluated, the data deliver a two-dimensional vertical cross-section of the strata under this line, and nowhere else. Frequently, a picture like that will not capture all the geological features of interest to us. As a result, the spatial geometry of the boundaries between the layers of rock can be only determined with a certain degree of inaccuracy.

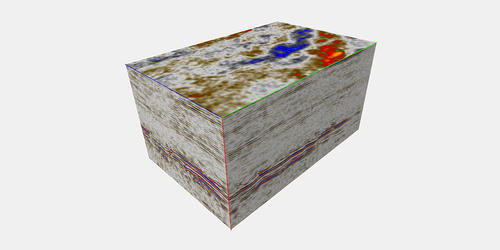

3-D seismics enables the seamless investigation of rock strata

3-D seismics, in which several lines of sound sources and geophones are positioned in a grid-like configuration, delivers much more meaningful results. The fact that the measuring points are covered in multiple ways from various directions enables a three-dimensional picture of the subsurface to be created. The information density in 3-D seismics is so great that the predictions are significantly safer than with 2-D seismics. 3-D seismics enables us to work from the surface to explore and generate a large-scale, detailed and complete picture of where underground rock layers are located.

Data interpretation provides the basis for future wells

Once the measuring process has been completed, our specialists start processing the data – a complex and costly business. Such huge quantities of data can only be processed quickly with the help of ultra-powerful computers. When these data sets have been completed, it is the turn of our geophysicists and geologists to interpret the seismic data and draw up profiles and maps of the underground rock layer boundaries. Such interpretations provide us with the basic information for identifying horizons in which a well could strike oil or gas.

Other processes complete the picture of the subsurface

The quality and resolution of the seismics are dependent not least on how well the waves can spread out underground. Salt domes, for example, are a huge obstacle that can hardly be penetrated by sound waves and thus badly affect the results. So in order to obtain a detailed subsurface model, our geophysicists also use specialist geophysical methods such as gravimetry, magnetics and electromagnetics.